Giovani Preza Fontes and Emerson Nafziger

Department of Crop Sciences, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign

The article was published at https://farmdoc.illinois.edu/field-crop-production/notes-on-soybeans-as-planting-gets-underway.html on April 10, 2024. You can also read this article in Portuguese and Spanish.

While statewide precipitation in March averaged 3.21 inches (89% of normal), we saw a clear north-south gradient within Illinois, with totals ranging from half to an inch above normal in the northern part of Illinois to as much as up to two inches below normal in the southern end of the state. April began with above-average precipitation across the state, with 7-day totals averaging almost 2 inches, or more than twice the normal amount. NASS reported that 3.7 and 1.9 days were suitable for fieldwork for the weeks ending March 31 and April 7, respectively.

The March average temperature was 5.5 degrees above normal in Illinois but with wild fluctuations. So far in April, temperatures have remained near normal in southern Illinois, and a little below normal in the rest of the state. The forecast predicts a steady increase in temperature over the coming weeks, with some chance of rain this week, and no major rains in the immediate future. This warming trend is likely to dry out soils and improve conditions for fieldwork and planting.

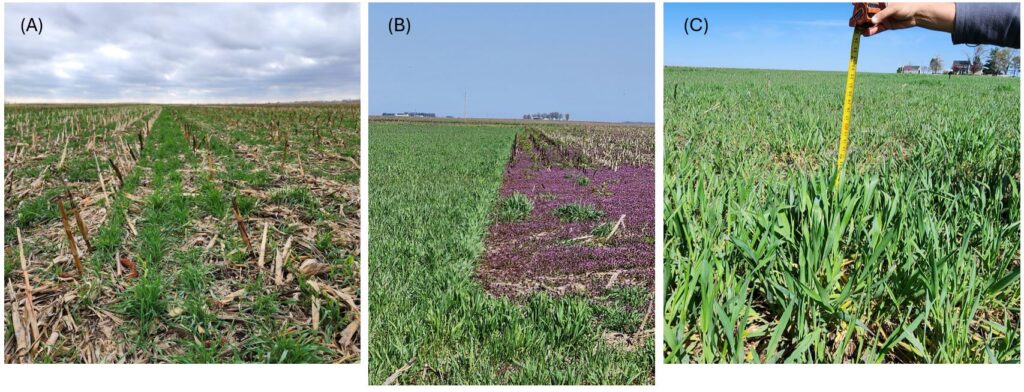

Cover crop management

The first three months of 2024 have been warmer than normal, and cereal rye has grown much more than usual, especially in those fields planted between late September and early October. Figure 1 shows cereal rye stands at the UI Dudley Smith Farm in Christian County, Illinois, on October 27, 2023 (Figure 1A) and April 8, 2024 (Figures 1B and C). The rye was planted into cornstalks on September 19, 2023, and got off to a good start in the fall. Most of the rye was 10 to 12 inches tall as of April 8. Cereal rye growth will speed up as temperatures increase in the coming weeks, and some thought might be given to termination timing before the crop gets too much taller. Rye planted later in the fall isn’t as large.

March 2023 was a wet month, and the cover crop helped dry soils out in April, but with little rain to replenish what the cover crop had taken up, yields were lowered in some fields last year. This illustrates one of the tensions in growing cover crops: we want enough growth to produce the expected benefits, but not so much that it interferes with the following crop. Terminating the cereal rye at 6 to 12 inches tall should provide enough biomass for erosion control, weed suppression, and keeping nutrients (especially N) in the field. Research in Illinois shows that about 500 lbs/acre of dry biomass can significantly reduce nitrate loss via tile drainage. Many experienced growers can successfully plant soybean into terminated cereal rye taller than 18 inches; letting the cover crop grow to this size may help with weed control, but it’s riskier in terms of crop yield, especially if soils remain dry.

Planting date

Conditions in some areas were warm and dry enough that prompted some people to plant soybeans as early as mid-March this year. Reports from NASS indicated that 1% of the Illinois soybean crop was planted by March 31, and 2% was planted by April 7. It’s not unusual for soybean planting to begin this early, but acreage figures for Illinois seldom appear this early. Rain this week has halted operations in some areas. Soybean seed now lying in cool, wet soils might still be able to emerge well, as long as it doesn’t stay wet. Cool temperatures slow the germination process and may extend the life of planted seeds, but they may not survive an extended period in saturated soil due to the lack of oxygen. Seeds can be subject to “imbibitional chilling injury, but only when the water they take up at the start is cold—around 40 degrees or lower. This condition can lead to abnormal growth and poor emergence, even if the seeds survive.

Our research shows that planting soybeans anytime between mid and late April is likely to maximize yield. Losses begin to pick up once planting is delayed into May: yields reach about 95% of the maximum by May 15 and 89% of the maximum by the end of May. yield. Yield losses continue to accelerate with further planting delays, to about 83% of the maximum by June 15. Most producers know from experience that high soybean yields depend more on what happens during the season than on when the crop gets planted, but late planting limits plant size and canopy development, and this usually lowers yield potential regardless of how favorable the season turns out to be.

The idea that early planting is needed in order to get the soybean crop to begin flowering before the longest day of the year (June 20 this year) has been much promoted in recent years. While April and early May are favorable times to plant, whether or not soybean plants begin to flower before the summer solstice is more related to May and early June temperatures than to planting dates. Soybeans need to reach about the V3 stage (3 expanded trifoliolate leaves) before they are capable of flowering. They also need a minimal night length in order to flower, with a longer night required for a longer-season variety than for a shorter-season variety. If a MG 3.1 variety growing at Champaign requires a night length of 9h:5m, it will get that first on June 8 as daylength is increasing (night length is decreasing), and then again on July 6 as night length is increasing. Warm weather helps the crop grow faster, and warm nights help trigger flowering, so warm weather in May and early June will often result in early flowering in a crop—especially one with relatively early maturity—planted in late April or even early May. If May weather is cool, early-planted soybean plants will not get large enough to flower by mid-June, and will need to wait until nights get long enough again in July. Flowering that starts before June 20 is often not very prolific, and it may be interrupted (presumably by having nights too short) for a week or so on either side of June 20, before full flowering resumes in July. An extended flowering period is favorable for yields, but the length of the flowering period depends on July and early August weather, and is not much influenced by how many flowers are on the plant by June 20.

Seeding rate

While 100,000 or even fewer plants per acre will maximize yield in many cases, our research shows that this is not always enough plants. Minimizing the seeding rate can end up costing yield and profit, especially when conditions lower emergence and stand establishment at or after planting. While responses to plant stand do vary across trials, we have found that 115,000 to 120,000 plants (not seeds) per acre at harvest are often needed to produce the highest dollar return on the seed investment. If we plant good seeds into good conditions, we can expect 85% stand establishment, in which case we should plant about 140,000 seeds per acre, which for most seed companies today is one unit of seed. We can tinker with that based on conditions at planting: lowering it by maybe 10 or 15 thousand if conditions and forecast are both favorable, expecting about 90% stand establishment. If the forecast is for heavy rainfall after planting, raising the seeding rate in anticipation of more stand loss may not be as effective as waiting to plant until the threat of heavy rainfall is passed.

A final thought

While there were clear advantages of having dry weather during the first months of the growing season the past two years, let’s remember that this helped yields only because, in both years, the dryness was relieved in late June/early July, and then again in August. The only certainty we have for 2024 is that it won’t be exactly like 2022 or 2023; each year brings a different mix of positives and negatives, whose effects are often not tied very closely to how the crop was managed. The best we can do is manage as if the season will be good, but not as if we need to use extraordinary management in order to cancel any negative effects of weather. In other words, we manage to set the crop up for success by starting with the basics, but trying to manage against “oddities” that the season might produce is an exercise in guessing, with low chances for success.